This New Type of Solar Cell May Revolutionize the Market

Despite the recent tariffs imposed on imported solar cells, the silicon solar panel industry has experienced tremendous growth for the past few decades. We have increased solar panel efficiency (measured in terms of how well a cell converts light into electric current) from below 10% all the way up to 22-23%. We have made them more durable, able to withstand decades of exposure to Mother Nature. Also, we have continued to innovate the manufacturing process, making them much cheaper to make than ever before.

However, it took nearly 60 years to get to where we are with silicon solar panels and we are probably pretty close to maximizing their potential. So, there may not be a lot more we can squeeze out of silicon panel technology. But, there is a new technology currently being tested and refined that is already at the efficiency level of silicon panels in a little over a decade.

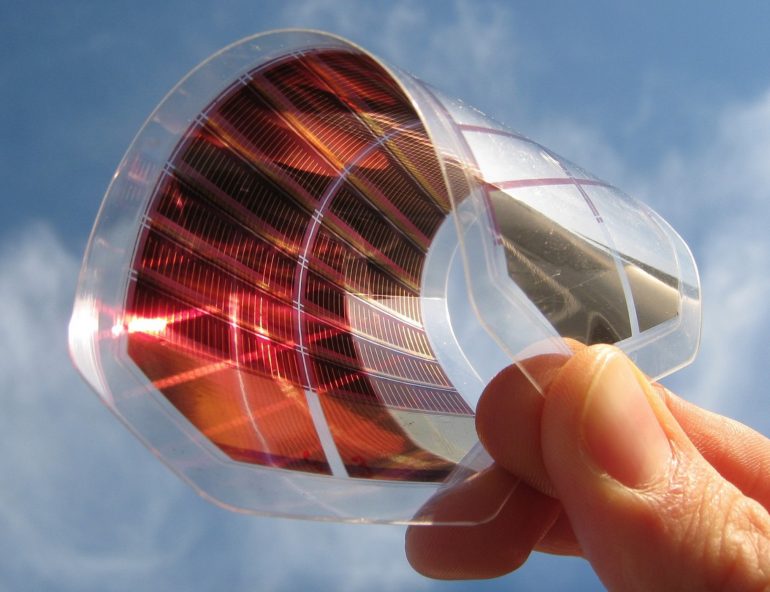

Perovskites solar cells have rapidly evolved into a promising technology, now with the ability to convert about 23% of sunlight into electricity. Which puts it on par with silicon solar cells. They are cheaply made from common industrial chemicals and metals and don’t require the intense heating of silicon panels. They can be printed onto flexible films of plastic in roll-to-roll mass-production processes. Silicon cells, by contrast, are rigid.

Perovskites we discovered by Russian mineralogist, Count Lev Perovski, in 1839. Their crystals are composed of 3 basic elements: calcium, titanium, and oxygen. However, It wasn’t until 2006 that it was discovered that this compound was also a semiconductor and could be the basis of a new type of solar cell. Since then, scientists have been testing and refining the compound to increase its solar efficiency.

The problem for perovskites right now is their durability. Like any new technology that is tested and refined in a lab, once they are exposed to a real-world application, it may not perform as well as in a controlled environment. For perovskites, once they were exposed to the extreme heat of direct sunlight for long periods of time or when they would be exposed to moisture, their cells would begin to decompose.

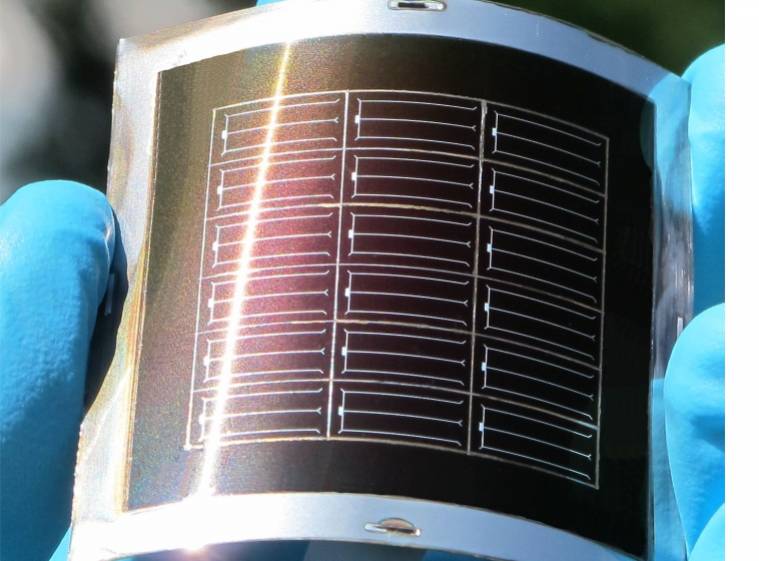

The goal now is to make the perovskites cells more durable to be able to be exposed to elements for two to three decades (the average lifespan of a silicon solar panel). That is exactly what the researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) are attempting to do.

NREL’s unencapsulated solar cell, a cell used for testing that doesn’t have a protective barrier like glass between the cell’s conductive parts and the elements, held onto 94 percent of its starting efficiency after 1,000 hours of continuous use under ambient conditions. The study represents an important benchmark for perovskite technology and its long-term durability.

In time, many believe that perovskite solar cells could become the most efficient solar cells on the market. They can already outperform silicon panels in low-light situations. Meaning they can produce more electricity on cloudy days than a silicon solar cell. And, they can be cheaply print in hours instead of having to be manufactured for days like most silicon solar cells.

One of the most exciting things about perovskites is that they are composed of many different compounds. This means that there are many different optical properties in the perovskite crystal. Many chemists believe we haven’t touched the surface of the potential efficiency of these crystals. Some believe by playing with the chemistry of these compounds, we might be able to achieve 30% efficiency or greater.

Perovskites are now a worthy opponent to silicon solar panels. However, it doesn’t necessarily mean they will overtake them. History is littered with great ideas and inventions that never hit the mainstream. Perovskites cells still have to prove to be durable over prolong exposure to environmental elements before you will see them on any commercial application. However, it’s undeniable that the technology is off to a very promising start.